When Glenn McDonald received his first computer at age fourteen — a silver Texas Instruments TI-99/4A that stored programs on cassette drives and displayed text through a connected television screen — he saw not just a machine but a box of “electrified possibility.” Armed with only a BASIC programming manual, he cobbled together his first software program: a stats-keeping application for his Dungeons & Dragons group. What had been a tedious exercise in pencil-and-paper calculation could now be completed with a few keystrokes.

“Somehow, I built a thing that made it possible for me to focus more on what I wanted that experience to be like,” Glenn said. “I could concentrate on spinning out this fantasy world for the role-playing, and didn’t have to spend as much time adding up bonuses and figuring out how many Kobolds would be killed by the glowing sword in the next six seconds.”

This early experience with computers shaped Glenn’s fundamental view of computers as tools to be molded to human needs and desires rather than rigid, pre-designed systems. “I had an idea from the beginning that the computer was something that you had to make useful for you,” he said.

Throughout his career, Glenn has served as a translator between computer capabilities and human desires. He views software as applied philosophy: a means of enriching the human experience by determining what one wants to accomplish in the world and figuring out how to get there.

Prior to joining Imbue, Glenn spent a decade as Spotify’s Data Alchemist, where he played a central role in developing and refining the platform’s music recommendation algorithms. Using machine learning and math, he evaluated the “subjective psychoacoustic attributes” of songs, distilling vast troves of music data into legible genres and genre-relations that helped listeners better understand and expand their music tastes. This became the core algorithmic force undergirding thousands of playlists including “Daily Mix,” “Fans Also Like,” and the highly-anticipated year-end Spotify Wrapped.

“My technical ability to write and tweak algorithms, and my cultural ability to assess the results in musical terms, that balance turned out to be kind of unique,” Glenn said. “It meant that I could make much faster progress on things than whole teams that had a lot more expertise on one side or another: a team of curators that had been radio DJs or record executives and knew the industry much better than I did but weren’t programmers and couldn’t tweak the algorithms; and machine learning engineers who could do very complicated technical things but couldn’t glance at [results] and have any idea whether they were close or far.”

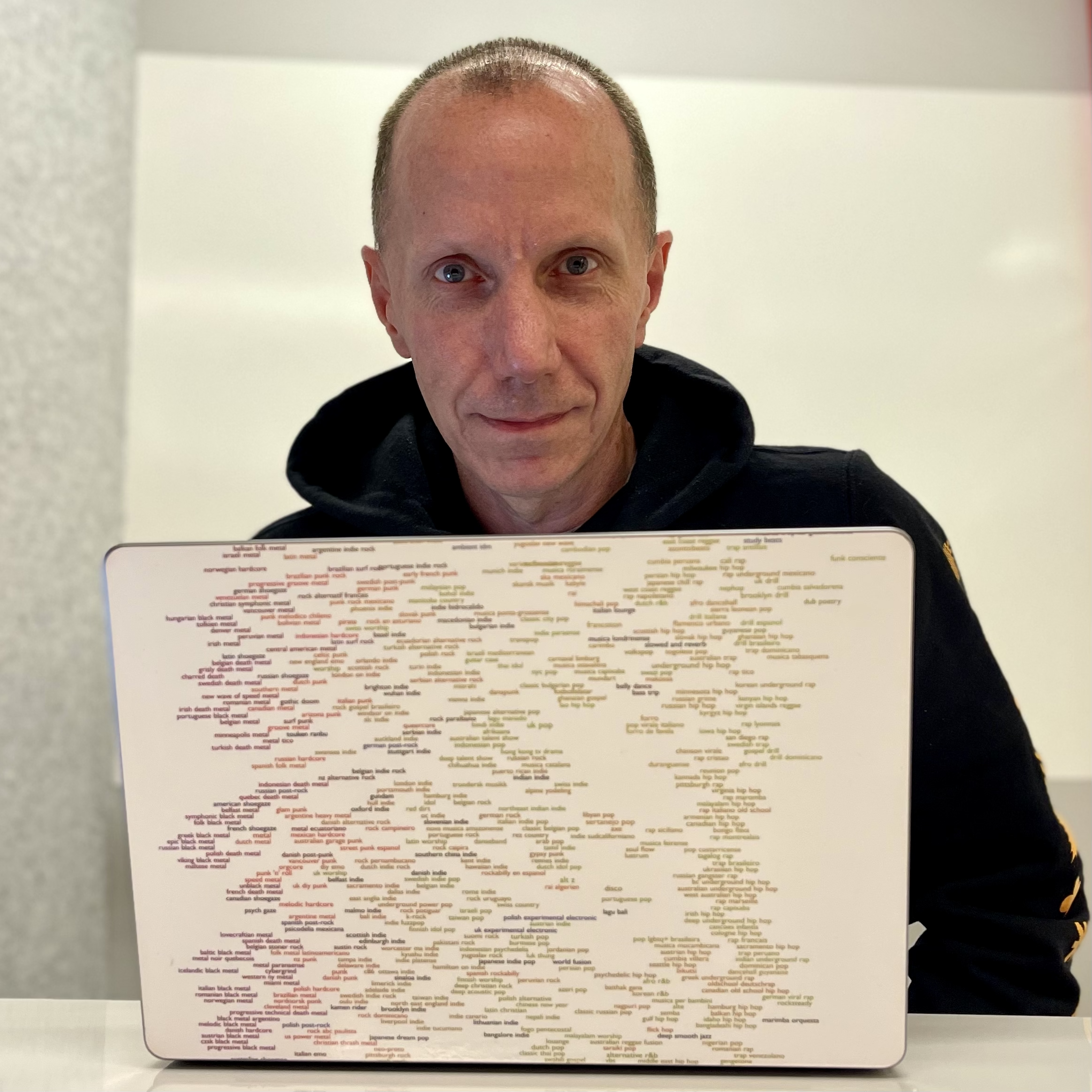

One of Glenn’s most beloved creations was Every Noise at Once, an algorithmically-generated map of 6,291 genres spanning ‘dungeon synth’ to ‘didgeridoo’ that was lauded by Billboard as “one of the most extraordinary sites on the internet.” Though he initially created it as a debugging tool while working at music intelligence firm Echo Nest (which was acquired by Spotify in 2014), it evolved into an essential tool visited by hundreds of thousands of people every month.

As Glenn writes in his book, You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song, Every Noise was an attempt to “give the music world back the insights and emergent self-organization that its collective music-making and music-listening produces.” Along with the main site, he also released a series of public research tools that anyone could use with their own Spotify API key to find new releases and analyze their listening history. Every Noise exemplifies Glenn’s vision of software as a tool for connection and discovery — fostering curiosity and serendipity rather than constraining the user to prescribed paths — that would eventually lead him to Imbue.

At Imbue, Glenn works to envision and prototype a new computing paradigm of “radically open software”: software that anyone can create, edit, and remix. He likens the ideal software experience to wandering through a new city’s streets without a map or destination, where every turn holds the possibility of unexpected revelations. It’s a return to the promise of the personal computer he glimpsed in his first TI-99/4A: not a device personalized by companies for users, but one shaped by individuals themselves.

Only with the recent advancement of AI capabilities has this vision of personal software become feasible. “Currently, our technical challenge [at Imbue] is: how do you go from human impulses at a higher level than programming languages to correctly functioning software?” Glenn explained. “It’s a problem space that only came into existence in the past two years, because there was no way to even approximate that before. No one had come anywhere near to human language as a programming input system.”

But this technical challenge is only part of the equation. Imbue’s mission, as he sees it, is not just to make tools that enable every person to create software, but to help people fundamentally reconceive of their relationship to technology.

“How do you get people to want to expand their music taste? is the same human question as, how do you get them to want different software?” Glenn said. “How do you get them to want to have a different relationship to their own information or to their online possibilities? How do you get them to demand openness from Facebook? That attitude of ownership, of possibility, of awareness of what should be my rights is not automatic.”

Technology, Glenn says, should not only increase our individual power, but also maximize the expressiveness of our efforts. He uses the metaphor of a hammer: the creativity of the act is not derived from how the nail is driven in, but where. In using a hammer, there is no lost expressiveness — the human determines the creative outcome; the hammer merely facilitates the process without dictating it.

“It’s not just, make any kind of software,” he said. “It’s [to] make a virtuous cycle, where the kind of software that we help you make helps you think more deeply about what you want, helps you collaborate, helps you share, makes it easy and natural for that software to be open, not just make more. We don’t want to make the next information-hoarding, doom-scrolling device more easily. We want to help you make things that will not be doom-scrolling — that will be profound more often than trivial.”

To Glenn, every big change in technology is an invitation to rethink the goal of technology in our lives.

“Humanity is the goal; the technology is a means,” he said. “If the technology is the goal, then you are satisfied with the technology — the gears spinning without squeaking. If humanity is the goal, the machine can be very efficient, but if it’s producing the wrong thing, then you have to fix it.

Our current moment, he suggests, presents us with a profound opportunity: to create tools that do not merely oil the gears, but radically expand our sense of possibility — for our software, for our lives, and for our collective future.

Read more about our work building coding agents in our Humans of Imbue profile on Bryden. If you are inspired by Glenn’s vision and want to develop a better way to create and edit software, we’re hiring!