RSS · Spotify · Apple Podcasts · Pocket Casts

Highlights from our conversation:

👁 “Vision is about the question of building representations”

🧠 “We (humans) likely have a 3D inductive bias”

🤖 “All computer vision should be 3D computer vision. Our world is a 3d world.”

Below are the show notes and full transcript. As always, please feel free to reach out with feedback, ideas, and questions!

Some quotes we loved

[05:52] Vincent’s research: “Vision is fundamentally about the question of building representations. That’s what my research is about. I think that many tasks that are currently not framed in terms of operating on persistent representations of the world would really profit from being framed in these terms.”

[08:36] Vincent’s opinion on how the brain makes visual representations: “I think it is likely that we have a 3d inductive bias. It’s likely that we have structure that makes it such that all visual observations that we capture are explained in terms of a 3d representation. I think that is highly likely. It’s not entirely clear on how to think about that representation because clearly it’s not like a computer graphics representation…

Our brain, most likely, also doesn’t have only just a single representation of our environment, but there might very well be several representations. Some of them might be tests specific. Some of them might be in a hierarchy of increasing complexity or increasing abstractness.

[15:32] Why neural implicit representations are so exciting:

“My personal fascination is certainly in this realm of neural implicit representations, it’s a very general representation in many ways. It’s actually very intuitive. And in many ways it’s basically the most general 3d representation you can think of. The basic idea is to say that a 3d scene is basically a continuous function that maps an XYZ coordinate to whatever is at that XYZ coordinate. And so it turns out that any representation from computer science is an instantiation of that basic function.“[21:17] One big challenge for implicit neural representations, compositionality: “Right now, that is not something we have addressed in a satisfying manner. If you have a model that is hierarchical, then inferring these hierarchies becomes much harder. How do you do that then? Versus, if you only have a flat hierarchy of objects that you could say, every object is separate, then it’s much easier to infer which object is which, but then you are failing to model this fractal aspect that you talk about.”

[26:08] The binding problem in computer vision:

“Assuming that you have something like a hierarchy of symbols or a hierarchy of concepts given a visual observation, how do you bind that visual observation to one of these concepts? That’s referred to as the binding problem.”[31:52] What Vincent showed in his semantic segmentation paper: “We show that you can use these features that are inferred by scene representation networks to render colors, to infer geometry, but we show that you can also use these features for very sparsely supervised semantic segmentation of these objects that you’re inferring representations of.”

[56:13] Gradient descent is an encoder:

“Fundamentally, gradient descent is also an encoder on function spaces. If you think about the input out behavior, if you say that your implicit representation is a neural network, then you give it a set of observations, you run gradient descent to fit these observations and outcomes, your representation of these observations. So gradient descent is also nothing else but an encoder.”

Show Notes

- Vincent biography and how he developed his research interests [01:52]

- Why did Vincent pursue computer vision research, of all things? [03:10]

- The paper that inspired Vincent’s idea that all computer vision should be 3d vision - Noah Snavely’s Unsupervised depth and ego motion [4:47]

- How should we think about scene representation analogs for the brain? [07:19]

- What Vincent thinks are the most exciting areas of 3d representations for vision right now: neural implicit representations [15:32]

- The pros and cons of using implicit neural representations, and comparing them to other methods (voxel grids, meshes, etc.) [15:42]

- How might we build in hierarchical compositionality into implicit neural representations? [20:14]

- Why is solving the problem of vision so important to building general AI? [25:28]

- Vincent’s paper on DeepVoxels . Why might they still use this method? [27:05]

- What areas of his research does Vincent think may have been overlooked? (focusing on computer vision problems rather than the AI problem) [28:51]

- How can we make scene representation networks more general? [30:36]

- Vincent’s paper on Semantic Implicit Neural Scene Representations with Semi-Supervised Training . How can we use inferred features from implicit NNs for sparsely supervised semantic segmentation? Why does it work? [32:19]

- If humans are able to intelligently form visual representations without a great internal lighting model, how might we build better “bad visual models” to better represent intelligence? [35:25]

- How might Vincent make for completely unsupervised semantic segmentation? [41:52]

- How might using 2.5D images be better than using 2D images? [42:31]

- How would we do scene representations for things that are deformable, rather than posed objects? [44:07]

- What unusual or controversial opinions might Vincent have? [47:57]

- Vincent’s advice for research [48:10]

- All computer vision should be 3D vision, not 2D & continuous representations seem to fit better [49:07]

- Why shouldn’t transformers work so well in theory? [51:03]

- Papers that affected Vincent: Noah Snavely and John Flynn on DeepView (novel view synthesis with neural networks), David Lowe on Unsupervised Learning of Depth and Ego-Motion from Video , Ali Eslamai on Neural scene representation and rendering ( steering the conversation towards unsupervised neural scene representation via neural rendering [53:18]

- Vincent’s Meta-SDF paper and his opinion on gradient descent as an encoder [53:35]

- What does Vincent think are the most important open questions in the field? [1:01:22]

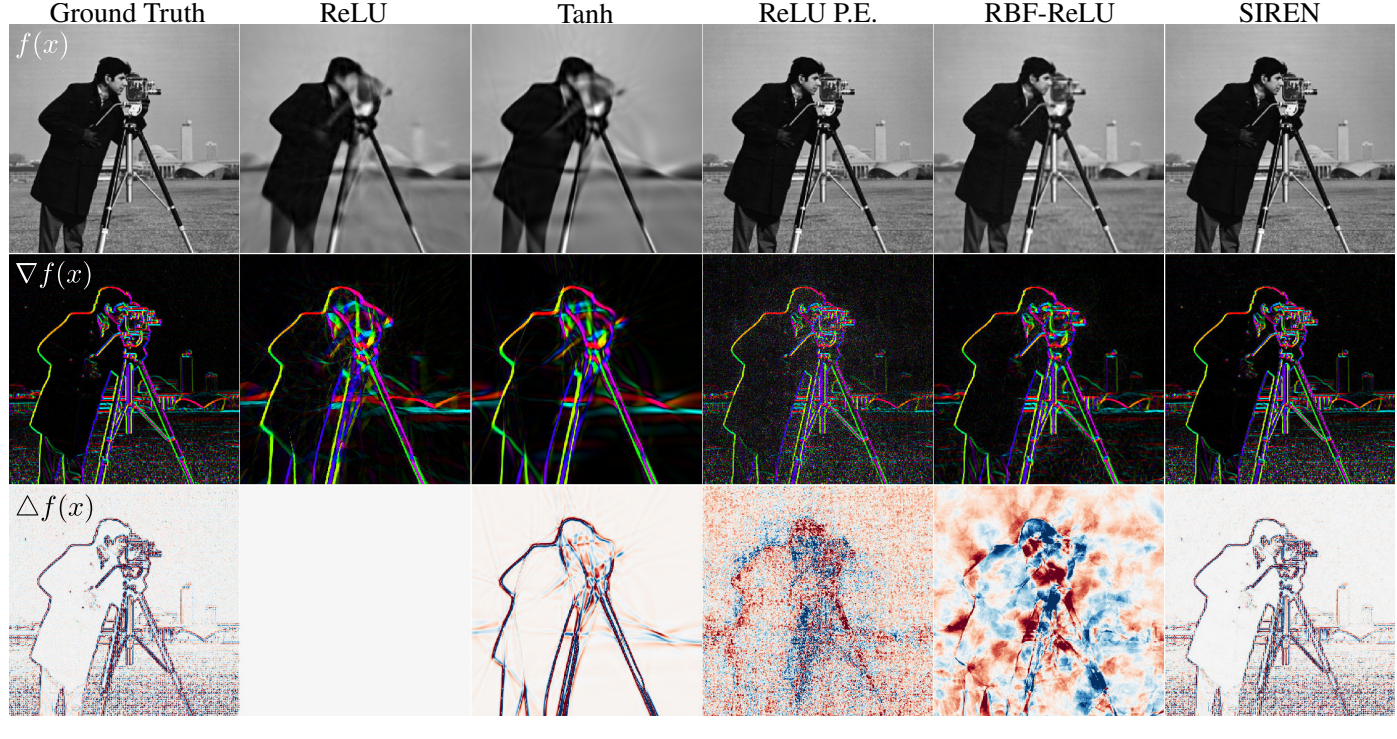

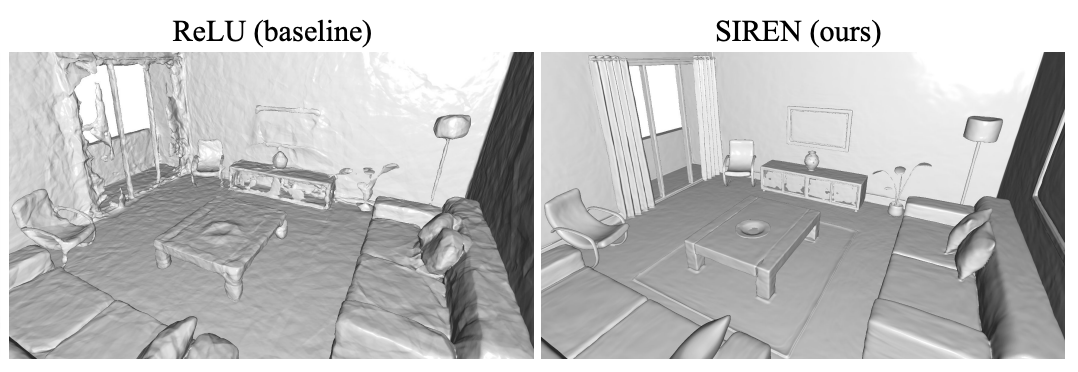

- What are the practical applications of SIREN? (sinusoidal representation networks / periodic activation functions for implicit neural representations) [1:02:59]

- Vincent’s thoughts on what makes for a good research environment and good researchers [1:04:54]

Transcript

Vincent Sitzmann: So, one of the opinions I had was this opinion that all computer vision should be 3D computer vision. That just fundamentally, our world is a 3D world, and every 2D observation that you capture of our world is just a 2D observation of an underlying 3D scene, and all kinds of reasoning that we might want to do, I think, fundamentally belongs in 3D. We should always go this path of first inferring a neural scene representation that captures properties of the underlying 3D scene before we try to do any kinds of inference on top of that, trying to understand what the scene is and so on. Those two things, of course, go hand-in-hand; inferring a complete representation of the 3D scene requires you to understand the scene.

Kanjun Qiu: Hey, everyone. I’m Kanjun Qiu, and this is Josh Albrecht. We run Untitled AI, an independent research lab that’s investigating the fundamentals of learning across both humans and machines in order to create more general machine intelligence. And this is Generally Intelligent, a series of conversations with deep-learning researchers about their behind-the-scenes ideas, opinions, and intuitions that they normally wouldn’t have the space to share in a typical paper or talk. We made this podcast for other researchers. We hope this ultimately becomes a sort of global colloquium where we can get inspiration from each other, and where guest speakers are available to everyone, not just people inside their own lab.

Kanjun Qiu: Vincent Sitzmann is a postdoc at MIT with Josh Tenenbaum, Bill Freeman, and Fredo Durand. He’s interested in scene representation, and his goal is to allow independent agents to reason about our world and to infer a complete model of a scene from only a few visual observations. I’d love to get a better sense of how did you develop your research interests? Where did you start and how did they evolve over time to where you are now?

Vincent Sitzmann: It’s an interesting little story. So, I started out, actually, not as a computer scientist but as an electrical engineer in my undergrad, and actually, I didn’t do anything related to computer vision in most of my undergrad. But I did do an exchange term in Hong Kong at HKUST, and that was the first time I was working with professors that were actively pursuing research and hiring students and so on. HKUST is very much like a research university, there I was taking a class on robotics, and I actually got a little bit into the math of rotations and Lie algebra, and that kind of stuff.

Vincent Sitzmann: And I found that extremely fascinating, and then when I came back to Munich, I figured that I wanted to do something that relates to that. Then I did my bachelor’s thesis in a group that is known for LSD-SLAM, which is a monocular SLAM algorithm. I spent most of my undergrad doing things like consulting and business tech intersection stuff, and I never really felt like I was getting the full nerd package. That was when I decided I should really try and do a complete deep-dive into something that I care about. During my bachelor’s thesis I had read all these papers from Berkeley and Stanford on vision. I had read about neural networks, I didn’t quite understand how they work, but I was like, “That sounds really cool. I want to do that.”

Kanjun Qiu: Hm. Interesting. Why vision, of all the things that you could possibly look at?

Vincent Sitzmann: It is an interesting question. It was just the thing that I got my in via the mathematics which I enjoyed. Maybe it could’ve been something different, it ended up being vision, but by now I feel very passionately about many things that relate to vision and I can tell you exactly why I think it’s a extremely fascinating topic. But I would be lying if I would say that back then I had that perspective.

Kanjun Qiu: I understand. Okay. So, you started to get your complete nerd package?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. And then I applied to the United States. I didn’t want to do research at first, I just wanted to take courses and then eventually do a startup. That was my original plan. But then I got admitted to Stanford, and Stanford I only took computer vision classes and machine learning. I started reading papers on 3D computer vision, and that was when basically, I really started to realize that that is something that I’m deeply fascinated by and that I have really strong opinions about this.

Vincent Sitzmann: I thought I should do research on this, but I wasn’t in the PhD program, I was in the master’s program, and there is actually no smooth change from the masters to the PhD, you just have to reapply. And honestly, I didn’t quite have the chops at that point, I wouldn’t have had the background to get into a PhD program at that time. So, I found my advisor, Gordon, and I told him, “Look, I want to do a PhD. Is there any research I could work on with you to basically get into this?” And so, we started doing research together, I wrote one paper. I applied to the PhD program, got into the PhD program and that’s how I came to do research, I guess.

Kanjun Qiu: And so, over this time, what did you discover about vision? What would you now tell us about vision, and why vision is interesting and your thesis on it, your perspective on it?

Vincent Sitzmann: Oh. This is a long topic. There’s so many interesting things about vision. The thing that back then was a little bit more low level, which I felt very strongly about, was that I saw all of these papers coming out that basically used convolutional neural networks, and that were all living in 2D. Whatever kind of properties they inferred, they always inferred properties that lived in 2D. But there was a few exceptions. So for instance, Noah Snavely at Cornell Tech had a few papers that I was fascinated by. The title of the paper with Peter Lowe is Self-supervised Depth and Ego-motion. And I thought, “This is the right way to go.”

Vincent Sitzmann: It all has to be 3D. There’s no reason why we should do any kind of vision in 2D, our vision is 3D vision, it seemed very obvious. If we ever want to get to more general AI, fundamentally for anything that lives in our world and that wants to interact with our world, vision is one of the first problems you have to solve. And I think that is one reason. Another reason for this is that, to me, vision is fundamentally about the question of building representations, that’s what my research is about. And I think that many tasks that are currently not framed in terms of operating on persistent representations of the world would really profit from being framed in these terms.

Vincent Sitzmann: So for instance, ConfNet, looks at an image, it predicts an action, and then it does an action and the image changes and then it predicts an action again, and so on, so on, not building a persistent representation of the underlying world. But if you try out a little experiment, you’re not sitting at your desks right now, but what you can do is you can close one eye and you can look around on your desk or wherever you’re sitting and you can look at an object. Then you can close your other eye, and you can reach for the object, you can pick it up. Most of the time that works right.

Vincent Sitzmann: And clearly, from this single, extremely impoverished observation that you have with your single eye, you infer a representation of your environment that encodes so much information about the environment. For this specific task, the geometry of the scene, like how far is the object way? What’s the shape of the object? How do I have to grasp it? How heavy is it? What material is it made out of? An infinite set of things that are all useful for you to execute this grasp. Making this explicit and really explicitly thinking about neural scene representations and operating on them, is an extremely fascinating topic.

Josh Albrecht: You mentioned that you’re working with some neuroscientists now. I think one thing that’s always interesting to me is knowing the analogs in the brain like, “How does this actually work there?” Do you have a sense for how explicit are those representations on the brain?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I guess I should relativize. I guess, I’m not directly working with neuroscientists, I’m working with people that are working with neuroscientists. I think the short answer is not really. We know extremely little on how the brain works, and specifically, on what kinds of representations the brain has. In fact, it is an ongoing discussion on whether this representation is even 3D. This is not a scientific consensus. There’s a whole spectrum of works that have evidence, either on the side that there’s clearly some 3D structure, to a degree that seems fairly obvious; but then there’s lots of work that argues that maybe the representations that our brain leverages are more like 2.5D representations. They don’t actually live in 3D, but you remember imprints of images, like key frames that you’ve seen and you retain some information about the geometry of these key frames. Long story short; no, I don’t have a good grasp on that at all. I do have opinions, but they’re not more than opinions.

Josh Albrecht: I’m curious what your opinions are, also.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. What are your opinions on this?

Vincent Sitzmann: These are opinions in the sense that I’m happy to be convinced otherwise. I think it is likely that we have, in fact even, a 3D inductive bias, by which I mean that I think it’s likely that we have structure that makes it such that all visual observations that we capture are explained in terms of a 3D representation. I think that is highly likely. It’s not entirely clear on how to think about that representation, because clearly, it’s not like a computer graphics representation. If you close your eyes, it feels differently than if you have your eyes open. With your mental eye, you can walk through your apartment, but it’s not going to be high-res photorealistic mental imagery, there must be information loss in there. The representation is much more high level than computer graphics representations, but I do think on some level there is a 3D-structured representation.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. It’s not a photorealistic 3D representation, but there’s some other kind of representations, that makes sense.

Vincent Sitzmann: I wont to take strong sides on this, but my feeling is that yes, it seems there is certainly some 3D structure. Our brain most likely also doesn’t have only just a single representation of our environment but there might very well be several representations. Some of them might be task-specific, some of them might be in a hierarchy of increasing complexity or increasing abstractness. And so, a gentleman called David Marr, who was an MIT professor, for instance, famously wrote this book called Vision.

Vincent Sitzmann: So, he made this point that there may be different representations at different levels, and there would be low-level representations; one of them would be the 2.5D sketch, which would basically mean that that is a rather low-level representation that you infer from the image observations that you take that only includes things like depth and maybe surface normals, appearance, texture, maybe low-level material properties, but that doesn’t yet have any of the semantic interpretation that you are conscious of. And then the argument would be that there’s another representation that you have that these 2.5D sketches are integrated into, and that vice versa also inform the interpretation of these 2.5D sketches.

Vincent Sitzmann: So that is one theory of how this works and I think, for one, this makes a lot of sense and I think this is always dangerous to do these experiments that you infer from yourself. But if you just judged from your own experience, certainly, it feels different when you close your eyes and you grab for an object versus when you have your eyes open and you grab for an object. And that, obviously, is not conclusive in any ways, but I think there is some evidence in this direction and it’s certainly interesting to think about, that maybe we should think about representations at different levels that might be completely different from another and separate.

Kanjun Qiu: If you were to think about, in the field of deep learning, the analog to this representations at different levels, do you feel like you have found or countered satisfying representations that might be reasonable analogs to some of these levels?

Vincent Sitzmann: I think that’s a really great question. So, one thing that I would say is that in several ways, convolutional neural networks, and I guess recently also, Vision Transformers are good candidates for inferring low-level information from images. It’s quite impressive, like monocular depth estimation, for instance, is one task where there are very satisfying results. And of course, there’re lots of problems with these approaches still, with respect to out of distribution generalization and questions like this, but it’s at least not entirely crazy to suggest that something like this could play the role of extracting low-level information, and then we use this information to integrate it into a more abstract 3D-structured representation.

Vincent Sitzmann: So yeah, I think ConfNets are a candidate for inferring these 2.5D sketches, at least, although clearly they can do much more. But then for the 3D representation, I think there’s lots and lots and lots of open questions that remain entirely unanswered. In the spirit of these multi-level representations that Marr discussed, potentially it might be a good idea to structure our models in the same way, maybe have rather low-level representations that potentially do not have a strict 3D structure only 2.5D structure, and then think of a way how we can integrate these low-level observations into a 3D structured representation, and how these two representations should inform each other.

Vincent Sitzmann: There is interesting experiments you can do that are very short and very funny that give you some evidence on how these things might work. Josh Tenenbaum, for instance, one of his favorite experiments is related to the Necker cube. It’s this wire frame cube, that you can look at the cube and you can force yourself to see it invert self. You know the ballerina who’s spinning and sometimes you can see her spinning in one direction and sometimes in the other? It’s one of these illusions and you can do this with a wire frame of a cork of a champagne bottle, it comes with this little wire frame that you have to take off, and you can do the same little experiment where you can hold it away from you and basically, try to focus on the side of the wire frame that is further away from you. And you can generate the same optical illusion where it looks like you’re inverting the wire frame.

Vincent Sitzmann: And then, very interesting things start to happen where you can start turning the wire frame in your hand, and it looks extremely weird because your brain seems to perceive the inverted wire frame. And if you were to observe the wire frame rotate in the way you’re rotating it, but it was inverted, that’s what you’re going to perceive. So, you’re going to perceive your hand turning in one direction but the wire frame turning in a different direction. There are some questions related to this because you can force your perception to perceive this 2D observation in different 3D interpretations.

Kanjun Qiu: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Josh Albrecht: Yeah.

Kanjun Qiu: It goes the other way, too. There’s a TED Talk that’s really interesting by neuroscientist Anil Seth, where he has a illusion of you look at this 3D grid with some shadows on it; so there’s a cube on it and a sphere on it and they’re casting shadows onto this black and white checkered grid. And colors of black look completely different because of the shadow on the grid, but the actual pixel value is the same. So, your brain thinks that these are different colors and but the value of the pixels is the same. Your expectation of the 3D scene actually changes the 2D perception of what the scene actually has.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I think there is a whole slew of extremely interesting optical illusions like that and many of them are related to this fact that the observations we record from our world are impoverished 2D observations but our world, fundamentally, lives in 3D and we use priors that we learn or that we have to basically do this inference of 3D from 2D, but sometimes it fails. And it’s funny to look for the cases where it fails.

Kanjun Qiu: Interesting. What do you feel like are the most exciting things in the field of 3D representations for vision?

Vincent Sitzmann: My personal fascination is certainly in this realm of neural implicit representations. It’s a very general representation. In many ways, it’s actually very intuitive, and in many ways it’s basically the most general 3D representation you can think of. The basic idea is to say that a 3D scene is basically a continuous function that maps an XYZ coordinate to whatever is at that XYZ coordinate. That’s your model you’re seeing as a function. And that’s fairly intuitive; if you look around and you just imagine that the scene is basically this function that maps the coordinate to whatever is at that coordinate.

Vincent Sitzmann: And so, it turns out that any representation that you know from computer science is an instantiation of that basic function. So for instance, a voxel grid is like a discretized version of that function that basically discretizes space into little cubes, and then in each cube, you can store something in the cube and you can say what’s at that cube coordinate. The point cloud, similarly, maps a set of a discretized points to something whatever is at the point. And now with neural networks, what we can do instead is we can say, “Well, we’re going to directly approximate that function by a neural network.” So, now we’re representing our scene as a continuous function that maps a 3D coordinate to a feature representation of what is at that 3D coordinate.

Vincent Sitzmann: And the reason why I’m so excited about this kind of representation is because it in principle has many of the properties that you would want from a general scene representation. So, for instance, whatever representation you come up with should be able to represent any kind of property that you’re interested in. It shouldn’t be limited to only representing properties that you handcraft or that you hand-engineer. Another important property of these representations is that they should really be volumetric because you can think about what is in front of your nose, you know that there’s nothing there, there’s air there. But you can think about that free space as well.

Vincent Sitzmann: Now, if you think about representations such as meshes which are often used in computer graphics, meshes only parameterize surfaces of objects, so you would really want something that can capture this volumetric aspect of 3D scenes. And then, another property that I really like about these representations is the fact that they’re continuous means that the memory you require to store this representation does not scale with the resolution that you want to store. With a point cloud or with a voxel grid, if you want a higher resolution, you have to store more points. But that’s unintuitive, right? If you imagine you have a white wall and the wall is completely flat and completely white, it actually doesn’t make sense to store more and more points to get a higher and higher resolution of the wall. Instead, what you want is you just want a closed-form parametric expression of the wall, so that then you just know it’s a white wall. That’s it. With these implicit representations, you can do that as well.

Josh Albrecht: That also begs the question, what are some downside of these implicit representations?

Vincent Sitzmann: They’re certainly things we have to figure out yet. I think that, in principle, one reason why I am excited about these representations is because it’s not yet clear that there is downsides that we cannot overcome. So, it seems that a priori there are no principled downsides that there’s just no way to get around, but there is plenty of challenges that we still have to overcome. One challenge is that these representations, by design, are not compositional. What I mean by that is if you look around on your desk, maybe there’s a few objects lying around on your desk, maybe a few more if you’re messy, you know that these objects are separate objects. You know that you can pick one of them up and you can move it around.

Vincent Sitzmann: Some people argue that representations that we should build for artificial intelligence have the same property; they should be aware of objectness and they should be aware that complex scenes are assembled from object-centric pieces. And I think that’s a very compelling argument, and one problem that we have right now is it’s very unclear how to do this with implicit representations. So, there is one way to do this where you just represent each object in the scene with a separate implicit representation, and I think there might be ways of figuring out how to do that. That’s a very interesting research direction, but if you do it naively, there’s problems with this because if you are interested in what is at a certain XYZ coordinate, you cannot sample all of your object-centric representations to find that out, because that’s not tractable. Imagine you have 1,000 objects in a room, you can’t sample 1,000 representations. So, you need some principled way of dealing with this, so that’s one of the big open questions.

Kanjun Qiu: Objects are a little bit fractal, not all the way down, but if you have a leaf, the leaf has a stem which is part of the leaf but the stem is also kind of a separate piece of belief. Or if you have a chair, it has a wheel and the wheel is part of the chair, but it’s also kind of its own separate object. Well, how would you think about that in this kind of object-centric view of complex scenes?

Josh Albrecht: Basically, what is an object? Where is that boundary?

Vincent Sitzmann: This is a very deep question; what is an object indeed? This is not a question that is conclusively answered as of now, so I think maybe a slightly more tractable question would maybe be how do you choose to model an object? One way of defining objects is to say, “Oh. We’re limiting ourselves to rigid objects,” like it’s a set of features that moves together according to rigid body mechanics. And then, if you now observe videos, that is a signal by which you can disentangle single objects from each other, so that is one way how you could disentangle objects. But with respect to this fractal property, that is a very acute observation, and right now that is not something we have addressed in a satisfying manner.

Vincent Sitzmann: There’s obviously plenty of people to think about this, and there’s ways of trying to build hierarchical models that explicitly model the hierarchy that you’re speaking of, but there’s lots of open questions on how you then do inference with these models. Like if you have a model that is hierarchical, then inferring these hierarchies becomes much harder. How do you do that then? Versus if you only have a flat hierarchy of objects where you say every object is separate, then it’s much easier to infer which object is which. But then you’re failing to model this fractal aspect that you talk about. I think the correct answer will definitely address this question, so whatever the correct representation will be, it will definitely include this aspect of modeling hierarchy in representations.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. One thing with hierarchy that always confuses me a little bit is, it’s so explicit and rigid. If we have a dresser next to a wall, and I put a picture on top of the dresser leaning on the wall, is this part of the wall, is it part of the dresser, is it its own thing? And then, I put a Post-it Note on that and I put another Post-it Note on that. They’re attached in such a strange and sort of brittle way and it’s like explicit hierarchy has always felt weird and unnatural to me. Are there any alternatives or ways around or is this just a necessary attribute of the world?

Vincent Sitzmann: I really enjoy talking about these things, these are very good questions. I have the same feeling that you have that predefining these hierarchies seems weird. And the reason is, actually, there is a fractal nature to this. One easy way to convince yourself of this is by just trying to think of something that you have never thought of as an object before as an object. So, for instance, if you pick up your water bottle, if it has some letters written on it, you can easily think of one of these letters as a symbol. And then, if you really wanted to you could be like, “Oh. Maybe it’s an R,” and the R has a little unfilled hole that you can even think of that as a symbol and then you can assemble these two like new.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. It does seem that the hierarchy has to be dynamic, to some degree. There are certainly mathematical models to model these kinds of things, and to a degree, maybe one very fundamental question is that the line that you’re straddling here, interestingly, is a very similar line to this question of connectionist representations versus symbolic representations. In the ’80s and the ’90s, that was a big question; how could we get to artificial intelligence? And there was symbolic AI approaches that dealt with symbols and logical expressions on top of these symbols, and then the connectionist models is what now in 2012 became the deep learning hype.

Vincent Sitzmann: And this question that you just asked, it seems that this hierarchy itself seems to be very well represented by something that is connectionist in nature. That is something that lives in a continuum, imagine a continuous feature space, and you can navigate that feature space and by virtue of navigating that feature space, navigate that hierarchy. But there are no models, that I’m aware of, that do a good job of discovering these hierarchies for the topic that we just discussed. There is a line of work that investigates continuous hierarchical latent spaces which is called hyperbolic embeddings that people have looked into in NLP, but basically there’s lots of unanswered questions on how to interface with these spaces. You still have the fundamental problem of if you have a scene and you have a scene with a discrete number of objects, how do you infer what level of the hierarchy they should fall into? Hmm. Actually, I think I have to think about this more.

Kanjun Qiu: Me too. Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: Me too. I don’t have a good answer to this question, that’s why I’m asking.

Vincent Sitzmann: So, this is something that I’ve thought about but I haven’t thought about this enough.

Kanjun Qiu: I was actually going to ask you, earlier you said you feel like vision is one of the first problems we have to solve if we want to get to more general AI. And what do you feel like are the biggest open questions that are currently in the way, from a vision perspective, toward a more general AI? If we solve 3D scene representation, is that good enough? Are there some questions that are really important, are there other questions beyond that? Do you have a sense of what the important questions are?

Vincent Sitzmann: I think I should clarify. So, what I mean when I say that vision might be one of the first problems we have to solve before we can get to more general AI, there’s still going to be lots of fundamental questions left as they relate to intelligence that vision will not make any dent in, so unrelated questions. For me, it’s been more a little bit of a thing where lots of the questions you have to answer in vision are extremely fundamental questions, such as this problem actually that we just talked about, in fact, is a question of how do you parse these observations that we have of the real world and match them to your inner model of how the world works?

Vincent Sitzmann: Another thing we just discussed is sometimes referred to as the binding problem, assuming that you have something like even a hierarchy of symbols or like a hierarchy of concepts, given a visual observation, how do you bind that visual observation to one of these concepts? And that’s referred to as the binding problem. If we can’t answer even these very fundamental questions that us humans solve so naturally, it just seems like there’s going to be significant problems that we will run into if you try to think about even more general things.

Kanjun Qiu: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think we agree with that.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. Yeah. Seems hard to make the claim that we can make something super-intelligent and still have no good answers to these very fundamental questions.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yes. And maybe that’s naïve, and I guess you could make the point that intelligence does not have to interface, necessarily, with raw observations of the real world. Maybe these are indeed separate problems, but maybe a different way of saying this is I believe we will figure out vision long before we will figure out general AI.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. I think that makes sense. Going back through your papers for a little bit and the history of these ideas, it seems like that’s sort of where you started, was this voxel representation, is that right?

Vincent Sitzmann: Do you mean, when I started with this question of scene representation learning or when I started with research in general?

Josh Albrecht: When you started with this question of scene representation.

Vincent Sitzmann: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. Deep voxels was the first paper there. Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: Do you feel like with that work there’s any reason to still use that approach or the things that have come after have sort of superseded that?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I think that’s a really good question. I think many of these questions that are about would you still use method X are really a question of the application you’re trying to go after. If your objective is to push forward artificial intelligence, then maybe deep voxels in particular, that approach might not be the most fruitful. However, if your application might be, “Oh. I want to do high-quality novel view synthesis, because I’m building a consumer product that has to solve that problem,” then that might be a completely different use case. That being said, many of the ideas that deep voxels introduced have now been absorbed into models that are, I think, fundamentally more powerful, although they also potentially come with different compute versus memory trade-offs and so on.

Vincent Sitzmann: So, for instance, after the scene representation networks paper that introduced these implicit representations for inverse graphics and for neural rendering, there has been this paper called NeRF. NeRF is a great piece of work that deals with a novel view synthesis of a single scene. So, you don’t want to learn prior, you don’t want to generalize across scenes, you only want to generate novel views of a single scene, so in a way it’s answering a computer graphics question. And that answers the same question as the buckles, and I think is a more powerful model.

Kanjun Qiu: I’m curious, what are some papers that you’ve published or work that you’ve done that you felt like was very overlooked? You thought it was interesting but people didn’t seem to get it.

Vincent Sitzmann: I think I’ve been somewhat lucky in that most of the papers I wrote someone found interesting. There are certain aspects of work that I have done that I think are more interesting than other people think.

Kanjun Qiu: Like what?

Vincent Sitzmann: We were talking about implicit representations. So, there’s a lot of focus right now to leverage these implicit representations to solve problems in computer graphics like novel view synthesis. Basically, I’m doing photorealistic rerendering of scenes, which I think is a super-interesting problem and it’s extremely useful, and it provides value, it’s a great application. But personally, the artificial intelligence angle is the thing that I find fascinating. Exactly these questions that we touched upon earlier like, “How do you model the fractal nature,” as you described it, “of objects?” And how do you build representations that are useful for artificial intelligence? That is the question that I’m fascinated in. But if you looked at the citations of scene representation networks, most papers aren’t that; most papers investigate the computer graphics angle.

Josh Albrecht: As I was reading the papers, I went back and I was like, “Oh. Scene representation networks. Yeah. I remember that vaguely from the past.” And I started reading through it and I was, “Wait a second. This is much more interesting to me than NeRF.” I also like NeRF, it’s so pretty, it’s so beautiful. It’s pretty elegant, too. But really, this other idea of like, “Oh. Yeah. Why should it go from XYZ to RGB? That’s a little bit strange. It should probably just go to some latent representation and just phase instead, that makes a lot more sense.” That struck me as a much more interesting idea from this perspective of more general artificial intelligence. Is there other work following-up on that, that you’ve seen and extended more in that direction?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. So, recently, there has been a lot more interest in this question of generalization, and people are starting to pick up these implicit representations and thinking about them in a framework for using them to solve problems for artificial intelligence, but most of that work isn’t yet published. But plenty of people are working on applications like that. Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: Well, I’m looking forward to next year’s there.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. Some things are rather just questions of let’s say we can learn the representations that we have right now. As limited as they may be, are they already useful to things like robotics, or physics simulation, and so on. So, one question is, certainly, can we just apply these things, including the generalization aspect, and what are these things already useful for? But then there’s also a line of work where people are interested in this question of compositionality and hierarchical representations, but no one has a good grasp on this yet.

Josh Albrecht: In terms of generalization, what are some ways of making scene representation networks more general that you think are interesting or promising?

Vincent Sitzmann: The most important question is certainly this question of compositionality. That is the way how to make it more general, in several senses. Other than that, there’s of course, other questions; we showed that you can use these features that are inferred by scene representation networks to render the colors to infer geometry, but we basically show that you can also use these features for very sparsely supervised semantic segmentation of these objects that you’re inferring representations of. There’s just a slew of things you can think of like what are properties of scenes that you care about? And then thinking of how could you model these properties in a similar way.

Josh Albrecht: That actually was one thing that seemed pretty interesting to me was that follow-up. I think it was inferring semantic information with 3D neural scene representations.

Vincent Sitzmann: That’s right. Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: I think it was kind of like, “Oh. How do you segment these different objects into different pieces?” But you could also ask about materials. It seems like you’d asked about all sorts of properties of objects like, “Is this thing alive? Is this thing deformable? Does this thing reflect light? Is this thing partially transparent?” There’s all sorts of things that you could ask and my guess is you could learn a lot of these things with very little data. Didn’t seem like the number of labels needed was very large, or that there was anything special about these labels or anything special about the architecture that allows you to learn those semantic segmentations, right?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I think that’s a good observation. Actually, another way to reframe the conversation we had earlier of this question of generalization, another way to frame this is to say that you really want to use these methods as a representation-learning approach. What you’re really trying to do here is not you’re trying to get a representation that allows you to render out new observations or something but instead, what you’re trying to do is you’re trying to set up a representation-learning framework that allows you to learn 3D representations, given 2D data that are already very rich in the information they encode. And if you think about it this way, that the reason why this semantic segmentation works, why it should work intuitively, is because if you infer the shape and the appearance of an object in 3D, then these are two features that are extremely valuable to semantic segmentation. So, it’s kind of intuitive that if you have a model that already faithfully reproduces color and geometry, that the features that this model has learned are useful to semantic segmentation as well.

Vincent Sitzmann: With respect to a question, there should be a slew of features that you should be able to learn from little data, I think that is fundamentally true. There are, however, lots of features that interact with these representations in ways that you would have to model in order for the model to discover them. An example of this is lighting. So, scene representation networks right now is exactly what we discussed before, it maps one XYZ coordinate to one color, for instance. But if you think about how lighting works or reflections, and view-dependent effects is what we call them, if you look around in your room and you have a strong light source, I’m sure you can find a surface that reflects something.

Vincent Sitzmann: And if you look at a point on that surface and you move your head, then the color of that point actually changes because they reflection changes. And so, if you wanted to learn the features that underlie that interaction, you would have to build a neural renderer that models this interaction in the first place. So, you would have to build a lighting-aware neural renderer. If you face these interactions for future work, there’s certainly one direction of future work which is about making these representations more powerful and more complete by improving the forward model of how the image is formed, conditioned on the 3D representation.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. One thing that’s always actually interesting to me with that particular example of lighting is, beats me. I don’t have good lighting model in my head and I’m constantly surprised by like, “Oh. Where’s that shadow coming from? Where’s that light coming from? Oh. It’s bouncing off my watch and going on to the ceiling.” I don’t have a very great, perfect realistic renderer or lighting model in my head, but I’m sure we can make neural networks where they took this into consideration and made really pretty pictures. But my question is more how we can do this really badly. The intelligence version of this is just something that coarsely approximate it but doesn’t mean to fully learn all the lighting and view-dependent effects, right?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. You could definitely put that into paper as it is. Because if you built a renderer that strictly enforces these things, then that means that the only way for your model to explain these things is to perfectly get them right. But as you point out that’s not what humans do, humans don’t get these things perfectly right. In fact, we’re terrible at getting these things right; if I show you something more complicated like fluid dynamics model, if I changed one of the parameters to make it not physically plausible, there’s no way you’re going to see that. But yet you have a dynamics model in your head that allows you to do pretty cool things like you understand if you have a cocktail that has different layers, you know exactly what’s going to happen if you stick a straw in and to start stirring. This is an open question.

Vincent Sitzmann: There are several ways to deal with this that we can think of like one of them is similar to what a GAN does; instead of trying to make the model explain the observation exactly, you’re trying to have it explained the distribution properly. It doesn’t have to generate the correct representation it just has to recreate something that looks right. It has to generate a plausible reconstruction, not the correct reconstruction. That’s one way, but it may very well turn out that there is something more fundamental to the thing you pointed out, where the question might more be that the model that we have in our head is not one that tries to match distribution, so it isn’t reconstruction-based model, but it just has a lot of approximations that are basically imprecise. And so, in that way it can still learn from this very complex data.

Vincent Sitzmann: Another way I sometimes like to say this is assume your brain has a 3D representation, encodes information about color and so on, and you can close your eyes and you can pull up something in front of your mental eye. But to generate that mental image is your brain doing ray marching? Probably not. So, I don’t know what the algorithm is, but your brain probably doesn’t have a ray march, right? Whatever the representation is, it’s probably also not exactly a 3D representation, it’s going to be something weird. But who knows?

Kanjun Qiu: It’s like missing a bat, try to turn it around in your mind. I’m just closing my eyes and visualizing right now, if I visualize a cube, I don’t realize that the cube has a back until I turn it in my head. So, my representation is very incomplete.

Josh Albrecht: Yours is more 2.5D, huh?

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. Mine’s 2.5D. I don’t know about yours. What you said about reconstruction is interesting. Maybe because many people in this field are approaching it from a computer vision perspective, people really optimize for computer graphics, people really optimize for good reconstruction. And in my mind, if we actually are interested in the intelligence perspective and generalizing, perhaps what we want is bad reconstructions because if we had perfectly good reconstructions, actually, we end up learning the wrong things, or not learning the more general patterns. Reconstruction is actually maybe not the right target for a lot of these vision models.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. That’s a very fair statement. One question that does come up immediately, then is, to a degree, when we learn these things, all we have is the image observations. Then, as we discussed before, maybe one alternative objective could be like matching distributions, maybe. But if you assume that what your reconstruction’s going to do it’s got to somehow reconstruct a bad version of the image, let’s say, for instance, then the question is what is that bad version of the image, and how do you come up with that bad version of the image?

Vincent Sitzmann: Another way of saying this is you want to match features. Let’s say you have an image and you want to match some higher-level features, we could use a pre-trained convolutional neural network or something to extract those features and then we could try to encode these features. But that would somehow be unsatisfying, wouldn’t it because then, how do you find the weights of the network in the first place? It becomes a little bit of a chicken and egg problem if you try to go away from basically matching the primary observations, then how do you get the thing that is not the primary observation?

Josh Albrecht: I’m not actually sure how different this is from reconstruction at the end of the day anyway but any different approach is things like maybe SimCLR or MoCo or other contrasts of objectives, where instead of reconstructing input, you kick things and shove them through some transformation and say like, “Is this thing that’s now transformed the same as this other thing that was transformed, or different from this thing that was transformed.” You can imagine doing that in a way that’s reasonable, like if I look away and then look back I can kind of remember what I was looking at before. “Okay. Is this thing that I’m seeing again kind of similar to the thing I saw before?” and in some weird transformation asking are these things the same and maybe somehow learn a contrastive or self-supervised approach that way?

Vincent Sitzmann: No. I think that is yet another way of how you could address that issue. Yeah. I agree with that.

Josh Albrecht: Or is it just reconstruction, GANs, and contrastive? Is there anything that we’re missing?

Vincent Sitzmann: Oh. I’m sure there is.

Josh Albrecht: Or anything like big categories of things that lots of people do. I’m not ask me about the things that haven’t been thought over invented yet, just the ones that are out there and commonly used.

Vincent Sitzmann: I mean, another thing that you could think of is like doing things like multimodal learning. The assumption being that you have two observations of the same thing, like you have an image and a description and then you’re trying to predict one from the other and vice versa. That is yet another way of learning representation, but I guess you could argue to a degree that’s still reconstruction.

Kanjun Qiu: Just a different modality.

Josh Albrecht: That’s sort of why I was saying that they’re all kind of connected in a way, even the contrasted ones are. You’re sort of reconstructing the transformed version or an internal representation of the version or it’s all reconstruction at the end of the day, it’s just what are you reconstructing. But I guess the whole set of questions also is interesting to me because, going back to the paper that got us down this rabbit hole in the first place, adding semantic information. One of the things that was really cool is, “Oh. It doesn’t take very many labels.” And a question I had was like, “Okay. How do you remove all of those labels?” I think that’s some of what we just talked about, but I was wondering if you had any other ideas of how do you made this completely unsupervised?

Vincent Sitzmann: I think that would actually already work. So, what you could probably do is you could just take these features and run a clustering algorithm on them, and then just label the clusters as semantic units. What we do in that paper is we just take only a linear classifier and train it on these features and then predict semantic class from that, and to a degree that tells you that that would probably work. Because these classes seem to be linearly separable, so not necessarily, but probably you could run a clustering algorithm that would retrieve something similar. So, I think that might already work. Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: One other question I had on both this and the previous scene representations is I think right now, how they work is they take posed 2D images, a number of posed 2D images of an object and then maybe work from that. How useful would it be to have posed 2.5D images as opposed to 2D images? Would that make it a lot better, or is it not really that helpful?

Vincent Sitzmann: It certainly helps a little bit. You can think of ways of saving compute by leveraging the depth information as well. But if you have lots of 2D observations of a scene and the scene is reasonably spatially varying, there is actually fairly little uncertainty in the geometry conditioned on the 2D images. You could just run something like COLMAP or classic multiview stereo algorithms to reconstruct the shape. So, in that case, the shape doesn’t help you much. It does help, of course, if there is uncertainty given the images. So, let’s say you have an object that has very sparse texture or isn’t spatially varying at all, then that would help to have depth as well.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. Maybe it could help having much less data, maybe many fewer example images.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I think one way to formulize this is to literally ask, “How much uncertainty is there in the geometry reconstruction given those images?” And you could certainly quantify this if you have something like shape data I don’t know and you have 100 images per shape in that car, the uncertainty is zero. There’s no uncertainty in the geometry given the image observations. But if you only have a single observation per shape car, then, at least for each car itself then certainly there’s uncertainty in the 3D shape given the image. And I think on that spectrum, you could figure out how much the depth would help.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. I think one place where that’s interesting to me is more deformable objects, a person walking around. Where you don’t get to like, “No. No. Wait. Don’t move. Let me walk around you and see what shape you are now. Okay. You can continue forward millimeter.” No. We kind of have to make estimates of those a bit faster. How would you extend this idea of scene representations to things that are deformable like that?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. So, there is some recent work building on top of NeRF that is concerned with, if you have lots of observations of a scene that changes over time, then you can parametrize it as a combination of one, a static scene representation, like scene representation networks, plus a warp field that is time dependent. It’s basically a vector field that just transports the features that are stored by your time invariant representation. For instance, if you have a face, you can just pick a canonical pose for the face and then you say, “Oh. Every facial expression I express as a deformation of that face.” That line of work does exist. However, I always have trouble thinking about what is our internal model for deformation? It seems that it is not quite that if you take a piece of paper and you crumple it, your mental representation of that piece of paper is not you register it as a flat piece of paper and then you try to reconstruct the way you crumpled it. That’s probably not what you do.

Kanjun Qiu: Hm. That does not seem to be what I’m doing.

Vincent Sitzmann: You do know that this was a flat piece of paper before, certainly you know that. This way of modeling probably just in general makes more sense for objects that can return to their previous configuration like a crumpled piece of paper. I guess you could flatten it again, but it can’t return to exactly the same configuration. But nevertheless, if I look at someone’s face, I don’t think I perceive their face as a deviation from their canonical face. I don’t know. Maybe we do all, who knows? But I don’t think that’s-

Josh Albrecht: My face deviated quite a bit.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. What it is then it is a little bit weird. There’s no work on this and I’m not saying that that’s how you should do it or that’s how it works, but one way that solves this is to basically say, “Well, your representation is always time invariant,” and if you meet someone, you just reconstruct their face in whatever configuration it is in that moment. And then this registration that maps the binding, as we had discussed previously, the binding that binds that observation to the concept of that person’s face, then, is the thing that realizes that this is the same face. You have a representation of the face and you understand what kinds of operations are permissible on that representation, and so you recognize the face as being in that general space.

Kanjun Qiu: It’s like instead of storing the information in the representation you’re storing it in this binding.

Vincent Sitzmann: I’m not even sure how much you reason about deformations. You certainly reason about deformations when you’re deforming something, but literally you’re trying to predict how something will be after you deform it. This is certainly an interesting question. I haven’t thought a whole lot about this. Yeah.

Kanjun Qiu: I’m just imagining a crumpled piece of paper in my mind right now, and I do not visualize a flat piece of paper and say, “Okay. These are the same thing.” I mean, I can make my brain do that but it’s not automatic. The first automatic thing that happens is somewhere else in my brain I realize, “This is paper. This crumpled thing is paper.” And so, there’s some representation of paper in my brain somewhere. This purple piece of paper is some formulation of this other concept in my head, and it really does feel like a different place in my brain. It’s really interesting.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I see exactly what you mean. I think you put it very well. Yeah. You recognize it as paper and you know that paper can come in other shapes and forms. But you don’t recognize that instance as a deformed instance of something else. Yeah.

Kanjun Qiu: Mm-hmm (affirmative). One of the things I was curious about as you were talking about your perspective on vision is what unusual or controversial opinions you feel like you have that maybe other people don’t seem to agree with or that are maybe undervalued.

Vincent Sitzmann: One of the questions on your list was, “What do you think makes a good researcher?” One of the points is that you can have the most fun in research if you do find things where you have opinions that are different than other people’s opinions. To a degree that’s obvious because if you have the same opinion as everyone else, then what’s the point? But maybe as a metapoint, also, how you pick your research projects, it can be most satisfying to pick research projects where other people think it shouldn’t work but you think it should. Imagine you execute perfectly on that research project, then no one will be surprised, so what’s the point? So, if you do something and everyone agrees, “Yeah. Obviously this sort of worked,” which is fine, we certainly need these kinds of results as well from time to time.

Vincent Sitzmann: Actually, this deformable thing that we talked about earlier, there’s six papers that appeared exactly at the same time because this idea was just in the air, everyone knew this should work. But with respect to the opinions I have is some of these opinions, I think, are by now mainstream. So, one of the opinions I had was this opinion that all computer vision should be 3D computer vision; that just fundamentally, our world is a 3D world and every 2D observation that you capture of our world is just a 2D observation of an underlying 3D scene. And all kinds of reasoning that we might want to do, I think, fundamentally belongs in 3D. We should always go this path of first inferring a neural scene representation that captures properties of the underlying 3D scene before we try to do any kinds of inference on top of that, trying to understand what the scene is and so on.

Vincent Sitzmann: Those two things, of course, go hand in hand; inferring a complete representation of the 3D scene requires you to understand the scene. But I think this is an opinion that, by now, lots of people still don’t necessarily think that’s true. And I think that’s good because, of course, we really don’t know. One important thing about research is that different people look into different things. Again, if everyone looks at the same thing, that would be very sad. It always strikes me that representations that are continuous seem to fit in my internal model of how the world should work much better. Meshes, for instance, that are discrete and discretized and are like sets that you have to reason over, that always seems a little bit weird to me. But recently there have been really great results with meshes as well, so certainly that’s possible.

Kanjun Qiu: Okay. All computer vision should be 3D computer vision and representations better-

Josh Albrecht: Make everything continuous.

Kanjun Qiu: Make everything continuous.

Josh Albrecht: Well, I think that’s part of why I like a bunch of these works is that that’s what they do. Yeah. Meshes have always struck me as brittle and hard to use or inaccurate but I think you’re right, there have been really good, interesting recent results for them. And the same, actually, with the all computer vision should be 3D computer vision. I mean, people have made image transformers and all sorts of other things but to me they’re like, “This is an insane way to think about images. You just turned it into a 1D array. Wow.” But it works so well, it’s very interesting.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I think one of the better arguments for why that maybe shouldn’t be the case is actually one that we touched on earlier. Remember when you said, it is weird that we as humans we don’t have a perfect forward model of how things like reflections work and so on?

Josh Albrecht: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Vincent Sitzmann: And the same could be true for 3D, as well. Maybe it is indeed the fact that our representation isn’t actually 3D-structured at all and instead let me turn it on its head; one argument for learning everything from data without any kinds of structure has always been that argument. Which is basically like, “Oh. If we just learn it from data, then we don’t have to make any of these hard assumptions.” We don’t have to assume that the world is 3D structured and our model can just figure out if that 3D structure were useful to the task, then it would find it. Generally, the issues that you run into here are issues of extrapolation.

Vincent Sitzmann: Another way of saying this is, I give you a data set of 2D images and they’re actually observations of shape that objects from different camera observations. And I even give you the camera poses, so it’s actually exactly the NeRF scene representation networks, just this general inverse graphics setup. If you assume a completely unstructured model, you could imagine something like an autoencoder; you take an image of the object, you encode it into a latent code, then you concatenate it with a view that you want to render of that object and then you decode it into that view. And you can train that and it’ll achieve zero training error on your training set. But then, what you’ll find is when you try to render novel views, the model hasn’t actually discovered the 3D structure at all. If you don’t make any assumptions on what the structure of this representation should be, there’s an infinite number of representations that could explain these observations in high-dimensional spaces, so why should it find the one that has 3D structure?

Vincent Sitzmann: All of these strong assumptions give us they give us guarantees on out-of-distribution generalization; if we assume it’s 3D-structured, then we can recover geometry from that, from just 2D observations for instance. Because we know it’s 3D-structured so we know it has to be multiview consistent, now you can get geometry out of it. The story isn’t at its end yet, maybe there’s ways of finding these inductive biases automatically, or we find algorithms that always look for the simplest explanation for a data set or who knows?

Kanjun Qiu: Earlier you said when you were earlier in your career, there were a bunch of other papers that really impacted you. What were some of those papers that you felt really affected you?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. So, early on when I was taking my first computer vision classes at Stanford, I was excited about reading anything from Noah Snavely at Cornell Tech and at Google. I later had the pleasure to collaborate with Noah, and that was fun, we wrote the MetaSDF paper together. But he wrote, I think, the first paper that did novel view synthesis with neural networks, this was called DeepView, I think, was the title of the paper. John Flynn was the first author on that. Then he wrote this self-supervised depth and ego-motion paper which was extremely inspiring to me because it was about how you learn depth just from video. That left an imprint because I saw these papers and then I was like, “Okay. So, we really don’t want to assume geometry.” So, when I started working on the deep voxels paper, our initial hypothesis was actually not what it ended up being, our initial hypothesis would be that we would also use depth information; that we would assume we have access to geometry and only later, did we realize that it’s way more interesting if you don’t have geometry.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. Definitely interesting.

Vincent Sitzmann: Let’s see, other papers that really impacted me. There was a paper from Ali Eslami et al. A science paper called a neural scene representation and rendering, which in many ways steered the discussion towards, “Okay. We can learn neural scene representations unsupervised via neural rendering.” I mean, who would’ve thought, right?

Kanjun Qiu: I’m really surprised.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. Very surprising. So, that was a great paper. One thing that started all this line of work on implicit representations which I then picked up for the purposes of inverse graphics… apparently this is also an idea that was in the air, was these three papers that came out called Deep STF occupancy networks, and IMNET. The title of the paper is not IMNET, but if you enter IMNET in Google, you’re going to find the paper. And that basically introduced implicit representations not for inverse graphics and neural scene representations and neural rendering, but for geometry parameterizing shapes as level sets of these neural implicit representations. That was extremely inspiring and inspired scene representation networks, for instance.

Josh Albrecht: And also, probably MetaSDF, I’m going to guess?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. The MetaSDF paper is an interesting one because with implicit representations, the space of your representation is a function space. Every instance of your representation is a function. So, what you’re really trying to do is you’re trying to learn a prior over a space of functions, and there’s different ways of doing this. In scene representation networks, we did it with a hypernetwork, and the autodecoder framework which was popularized, I would say, in the Deep STF paper. Other ways of doing this is with an encoder; you could take an encoder that takes an image, produces a latent code and then again you could use a hypernetwork to map that latent code to the parameters of your implicit representation.

Vincent Sitzmann: But fundamentally, gradient descent is also an encoder on function spaces. If you think about the input/output behavior, if you say that your implicit representation is a neural network, then you give it a set of observations, you run gradient descent to fit these observations and outcomes, you’re a representation of these observations. So, gradient descent is also nothing else but a encoder, it’s just very different architecture than convolution neural network that takes the image and outputs the weights of your neural network. But fundamentally, it’s just a function that takes some things as inputs and outputs the weights of your neural network.

Vincent Sitzmann: Gradient descent is also just an encoder. Thinking about it in that framework, I think MetaSDF is very easy to think about metalearning, then, because you’re saying, “We want to have as output a function, so we’re just trying to have some sort of encoder that we can give the observations and it gives us the function that we’re looking for.” Okay. We’re just going to use gradient descent for that. The key contribution of the Mamo paper, which is what this is built on, was to say, “Well, we can back-propagate through the gradient descent optimization, and then optimize the initialization to be easily specializable.” I think this was also completely unrelated to the question you asked about MetaSDF.

Kanjun Qiu: No. It’s actually really interesting.

Josh Albrecht: That’s okay. It was a prompt to talk about the paper. I thought it was a really interesting paper. I think my question was irrelevant, also, it was just, “Oh. Why did you think it was out there?” I think it was a perfectly valid use of how you were thinking about and I think this answered the question. It is a interesting way of viewing gradient descent as an encoder. I never really thought about it like that before-

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. I think that’s a really interesting representation.

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. I also like this views because it really allows you to think about the different trade-offs of the different encoders. If we go back to scene representation networks where we use this auto decoder framework where you say every 3D scene in your training set gets its own latent code and you translate the latent code to the weights of a neural network with hyper network. And then, at training time, you’re just optimizing jointly the weights of the model together with all of these latent codes. At test time, the way you do inference is you get a single observation of a 3D scene, you fix all the weights of your model and you initialize a new latent code, and then you back propagate into that new latent code until it fits your observation.

Vincent Sitzmann: So, you can also frame this as a function encoder, now you’re just using gradient descent without any metalearning. I think it’s valuable to think about it in the same framework because it tells you the pros and cons. If you use a convolution encoder, you are bound to a certain resolution, and to having your observations lie on the regular grid in the form of an image. And you will have no flexibility in this; if you have a convolutional neural network that is trained at a certain resolution, you have to give it images at the same resolution. You can’t give your convolutional neural network single pixels, that’s not going to work. So, you always have to give it a full image. If you instead, think about gradient descent, gradient descent doesn’t have that constraint. With grading descent, if you do this optimization, you can operate on an arbitrary set of pixels or on the full image or images at arbitrary resolutions. It doesn’t matter because your encoder is agnostic to the image resolution.

Josh Albrecht: And then, what’s the other side of the trade-off?

Vincent Sitzmann: For gradient descent in general, the downside is that if you use gradient descent without metalearning, then it takes very long because you have to run optimization to find that latent code that takes on the order of minutes for scene representation networks. While if you have a convolution encoder, that it takes milliseconds. If you’re interested in this, you can look into questions like meta-overfitting and things like that. But maybe the most high-level overview is to say that metalearning can also overfit to your training set, it’s going to have a hard time reconstructing things that are very different from the training objects or those training sets.

Vincent Sitzmann: That’s the same for all algorithms that we have found so far. And then it’s very expensive. You can make it cheaper but if you make it cheaper, it’s a different algorithm that behaves differently yet. Then there’s different questions about what solution it finds again, there’s the second order metalearning algorithms and first order metalearning algorithms, depending on whether you back propagate through the gradients themselves. Because in metalearning in the forward pass, we run gradient descent, and then in the backward pass we have to take the derivative of the output of gradient descent with respect to its inputs, and that encompasses taking second order derivatives, which is very expensive in PyTorch and in TensorFlow. Somewhat cheaper in Jax, but still it’s very expensive. And then there are first order metalearning methods that just ignore the contribution of these second order derivatives, but these behave completely differently.

Josh Albrecht: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What’s your feeling about this after the paper? I sort of hear a hint of, “I don’t know if I want to use metalearning again.” But I might be reading into your statements.

Vincent Sitzmann: Oh. No. No. I think metalearning is extremely exciting. I will definitely use it again. There’s just so many open questions there that I have not had the time to look into. But for now, I have so many questions that are in my field that I don’t see myself getting to these questions.

Josh Albrecht: Mm-hmm (affirmative)

Kanjun Qiu: That makes sense. What do you feel like are some of the most important open questions that are in scope right now?

Vincent Sitzmann: Certainly, this compositionality question. Answering questions on how can we build models that learn things about lighting for instance, and that learn things about basically any aspect of the real world that we interact with. There’s the question of applications, and there’s the question of the representations themselves. My research revolves around these two broad directions; so one of them is how can we make the representations themselves better? And these are the questions we touched upon, asking questions like how can we make them compositional? How can we learn more features? How can we model more properties of the real world?

Vincent Sitzmann: And then, the other side of the coin is, of course, once we have these representations, what are we actually doing with them? And certainly, one set of applications already is being explored, which is computer graphics, and in computer graphics these representations are already providing very significant value. But then, say robotics, if you want to grasp objects, can you leverage these representations in some way there? Or physics simulations, we show that you can use these implicit representations to parameterize solutions to partial differential equations. Is that useful somehow to fields where you have to solve these kinds of problems? Another lens to look at this is that the tools that I’m using are basically tools from 3D Computer Vision, computer graphics, and artificial intelligence. Whatever contributions I make usually lie at the intersection of some of these, or just in one of these proper.

Kanjun Qiu: That’s a really good framing.

Josh Albrecht: No. I was going to ask just in terms of actual applications, and I know you mentioned SIREN but actually one of the things that, as we read that paper a long time ago, it was very exciting, all the results look really cool. And then, at the end we’re like, “Wait. But what do we use this for?” Because I was like, “Oh. We fit to this particular image.” Like, “When will we ever fit to a particular image or a particular scene like this?” I mean, I know it’s super-useful, so I was wondering can you help explain to me exactly where and why this is useful, any applications?

Vincent Sitzmann: Yeah. Oh. Absolutely. It’s a great question. So, the side of SIREN that I think might be immediately useful to downstream applications might in fact be solving partial differential equations. So, for instance, this retrieving the signed distance function of a scene given its point cloud, that is useful. But then, for all of these other signals that you mentioned, why would you want to parameterize an audio signal via an implicit representation? And again, I think there the question is what’s your application? If you want to play the audio signal, then who cares?

Vincent Sitzmann: If you want to express priors over audio signals, or if you want to have artificial intelligence interface with audio signals, then the question comes up, what is the representation that is amenable to being interfaced in this way? And I think that’s where the exciting things of SIREN line. In the same way where scene representation networks use these implicit representations to learn priors over 3D scenes that were resolution-independent and you could render it at arbitrary resolutions and the memory they require only scales with the complexity of the underlying scene. In the same way, you could use SIREN, and people have used SIREN in this way to learn an adversarial model that is resolution-independent on images. If you parameterize images in this way, now we have this toolbox of hyper networks that generalizes across these representations, which are then resolution independent.

Kanjun Qiu: That makes sense.